TL;DR

- Moving code and data sections to huge pages increases application performance without any source code modification. We are able to get +10%.

- It’s possible to quickly estimate the effect for your own project without any recompilation at all, details are here.

- The final solution utilizes “classic” huge pages (not transparent huge pages), that’s why it could be referred as a next generation of

libhugetlbfs.

Introduction

If you ask an engineer how to solve your performance issue, the answer will depend on the engineer specialization.

- System architect opens the product documentation trying to find the bottleneck component. Replacing it should breathe new life into the whole system.

- SDE immediately asks the access to the source code, then apparently he gets lost for the next couple of months analyzing the algorithmic complexity - maybe someone missed suboptimal “quadratic” piece of code or even worse?

- SRE starts with profiling the core system processes, analyzes how they communicate with the OS kernel, how the memory is used:

perf top/perf stat/perf record/perf report/jemallocprofile orpidstat/vmstat/sarorstrace/gdb. If more or less up-to-date Linux kernel is at hand, then eBPF helps a lot. The result - a list of the heaviest functions and what mostly troubles OS (lack of network / disk bandwidth or RAM amount?). - A compiler developer opens the brave new world of profile guided binary code generation: PGO / AutoFDO / BOLT. He definitely offers LTO to strengthen the effect. It has been proven many times that applications become much faster, especially when non-x86 platforms are used. Recently all these technologies show incredibly outstanding results, working without any source code modification. Attractive, isn’t it?

- A hardware specialist opens up the doors of NUMA-aware architectures. Let’s be honest, we have been using the NUMA servers for years, meanwhile we still have a great faith that all CPUs are equal and all RAM has the same access speed. By the way, “Random Access Memory” is a relic term from previous century, today it’s just an illusion. The set of L1/L2/L3 caches + RAM which belongs to a particular NUMA node - the further the memory is, the slower access, more complex hardware synchronization. Forget about gigabytes of RAM installed into your server, if you need the real performance, imagine that all your memory is extremely simple, predictive, with sequential access, exclusively owned by the executing thread and the amount of it is extraordinarily small (a couple of megabytes?). It’s really tough to apply all these knowledge to a particular project, but it’s definitely worth trying to do it.

- A OS developer, which has a terrible burden of backward compatibility, certainly tells you stories about petabytes of production ready applications, then he opens your eyes to amazing new APIs for asynchronous NVME access (

libaio,io-uring), tasks schedulers for clouds (Linux kernel >= 4) and technologies for optimizing the virtual / physical address translation.

The range of available tools and technologies is quite big, today I’ll tell you about our experience of applying huge pages using the MySQL server as an example. Here we improve CPU utilization via virtual to physical address translation optimization.

There’ll be no stories about OS virtual address subsystem and how it’s implemented inside the Linux kernel, what is the MMU and TLB. There’re a lot of official articles all over the Internet and excellent books where all the theory / practical approaches are described in details. If you forget about anything, refresh your knowledge using your favorite book about modern operating systems.

Of course, the huge pages technology isn’t new. How many decades have gone since the Linux 2.6.16 release? However, the number of products using it is vanishingly small. For example, in MySQL server huge pages might be used for the InnoDB buffer pool (internal B-tree cache), wherein it’s implemented over the old SystemV shared memory API, which requires additional specific OS configuration.

Ok, even employing old APIs is good, but where’re the applications which seize the opportunity to exploit huge pages for their code and data segments? E.g. .text/.data/.bss are located into the standard process address space, which might be mapped to the huge pages too. If application has huge .text/.data/.bss segments, the access to them suffers significantly from iTLB/dTLB misses. I think the number of vendors who really uses such approach could be counted on the fingers of one hand. The relevant code examples I’ve found so far:

- libhugetlbfs: the

remap_segments()function - Google Chromium: the

RemapHugetlbText*()functions - Facebook HHVM: the

HugifyTextfunction - Intel Optimizations for Dynamic Language Runtimes: the

MoveRegionToLargePagesfunction

Nevertheless, all related published papers have equal conclusions: the applications become faster if code and data are moved to the mappings backed with huge pages. That’s why our team decided to conduct our own research in this field.

The theory here is pretty simple: the larger the page, the bigger address space could be covered by TLB. As soon as the number of frequently used pages exceeds the number of TLB records, the performances drops dramatically. By the way, modern CPUs has several TLBs, usually in L1 and L2 levels. In this article the benchmark is described which shows the performance impact of L1/L2 TLB misses for the exact CPU. Moreover, different CPU architectures support different set of huge pages. E.g. x86_64: 2M, 1G; ppc64: 16М; AArch64: 64K, 2M, 512M, 16G (depends on CPU model and OS kernel configuration). That’s why the decision what page size to choose is determined by the particular application and the problem it solves. For MySQL server 8.0 the code and data segments have size about 120 MB (not too big). For our goals, only x86_64 and AArch64 are important, therefore we picked the default 2 MB huge pages.

The next question is what huge page technology to choose? The Linux OS offers:

- classic huge pages

- transparent huge pages

Good old Morpheus comes to mind here

- The blue pill (transparent huge pages) - you turn on the technology in the kernel, then you prepare correctly aligned memory mapping and recommend the Linux kernel to use it. That’s all. After you “wake up in your bed and believe that everything else was just a dream”.

- The red pill (classic huge pages) - you dig further and figure our “how deep the rabbit hole is”.

The easiest way is to take the blue pill. However, we were seriously concerned about the Percona experience in THP usage for generic databases. So, the pitfalls:

- Physical memory defragmentation. Have you ever noticed the “khugepaged” process? It could suddenly stop your application even if you never planned to use any transparent huge pages at all. It relocates the processes all over system during the defragmentation. Even the major huge pages consumer (like MySQL server) endures sporadic spikes in TPS/latency during that process.

- Unpredictable behaviour. What’s the life’s bright hope for all DBAs? That’s correct: the technology stack must be lightweight and simple, the system must be predictable and fast. THP is the kernel optimization. It might provide the performance boost, or it might not work at all, or it could work temporarily (in some cases), or it could work all the time, but with some limitations, and only the concrete version of kernel knows what’s going on. High quality performance estimation is a hard job alone, meanwhile performance estimation of the kernel optimization is much, much harder. Of course, if you are the Linux kernel developer, it’s not a problem, but in that case I doubt you read my article :)

- Swapping. Older Linux kernels split a huge page into default pages before dumping it to the disk. When the huge page is loaded back, the bunch of default pages merges together into one huge page. Obviously, this process hits the performance badly. Classic huge pages are allocated in RAM permanently, they never go to

swap. At the time of writing these words I saw the Linux kernel patches which solve this problem. - Memory consumption growth. Even if only a couple of kilobytes is needed, we still allocate the full huge page (e.g. 2M). I agree, that this’s the common symptom for both classic and transparent huge pages, but the programmer don’t have any control over THP at all. All publications keep mentioning this issue regularly, so I decided to follow the tradition and to add it too.

I must admit, that the Linux kernel improves the THP in each release, and in the near future the whole situation may fundamentally change, maybe even the future is already here. Anyway, Google/Facebook/Intel widely offers THP in their solutions for a reason. However, our team wanted the result right here and right now, moreover changing the Linux kernel on production servers takes quite a lot of time.

So, we took the red pill.

Where to begin?

I believe, every team who tried to remap code and data segments to huge pages got started having life-fire compat training with libhugetlbfs. This library is extremely ancient, supports huge variety of Unix-like OSs. If we speak about Linux - very old kernels (2.6.16) and toolchains. I suspect it was designed originally for small embedded systems powered by non-x86 specialized processors with extremely tiny amount of RAM on board. Anyway, if you’re interested in touching the life history and gaining more wisdom - welcome to the project site.

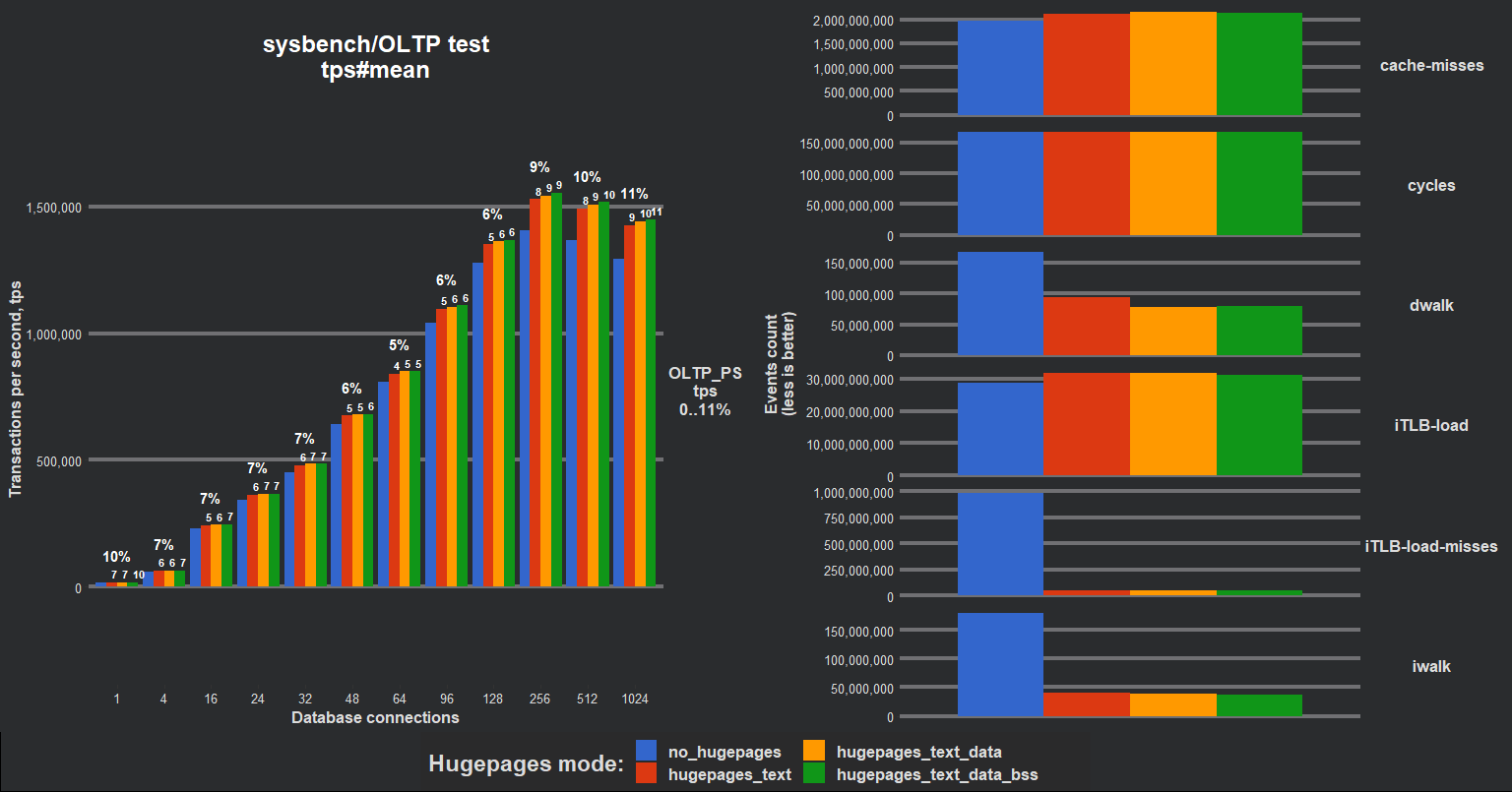

Exploiting libhugetlbfs is undoubtedly an uneasy job which takes quite a lot of time, however, the resulting speedup was undisputed. MySQL server produced +10% additional TPS (transactions per second) in OLTP PS (point select), 1vCPU virtual instance, Linux EulerOS, x86_64. iTLB-misses became several times lower. AArch64 platform showed even bigger performance improvement. Our team additionally researched the remapping text/text + data/text + data + bss segments, the result is represented in the following chart (AArch64 CPU: Huawei Kunpeng 920):

Of course, it was high loaded CPU-bound benchmarks (“serious CPU starvation”), nevertheless +10% definitely worths further research. Along the way several issues/restrictions appeared:

- Turning ASLR on the server (MySQL default compiled with PIE) caused SIGSEGV. Following investigation revealed the clear bug inside

libhugetlbfs, which was immediately reported (with the fixing patch applied): https://github.com/libhugetlbfs/libhugetlbfs/issues/49. After a year I was notified that the testing team can’t reproduce the problem. I’m grieving… - Maximum number of segments which might be remapped is 3. I think the reason is in the history again, GNU BFD linker used to generate 2 LOAD ELF segments only (“r-x” and “rw-“), so the limit of 3 has sense. However, the recent security requirements made it a bit smarter - now it generates a separate LOAD segment for constants (“r–”) by default. At the same time, the GNU BFD linker isn’t that smart, looks like it cut the read only segment off the both “r-x” and “rw-“ segments. As a result, the 4 LOAD segments are generated, so only first 3 segments are remapped and the last segment, which is usually the biggest one and contains the

.dataand.bss, is left untouched. - If you conquer the previous problem and force linker to produce 2 LOAD segments, you notice that when the last LOAD segment is remapped, the HEAD segment simultaneously disappears from the virtual address space. It slips through your attention without any warnings or errors, the system call

brksimply stops servicing the users (always returnsENOMEM). Affects onlyglibcwhich usesbrkfor small allocations (less than 128K). After the accident, theglibcswitches tommapsystem call for all allocations. It’s unsure for me how this troubles the performance and the system in total, if you know, please, share your ideas and knowledge in the comments. P.S. Tested, thatjemallocisn’t affected, since it usesmmaponly. - There’s no easy and robust integration into application - all the job is done in the DSO constructor without any logs. If error happens, the application doesn’t start. Figuring out what was the reason of failure takes time.

hugetlbfsis used as API for huge page allocation. You must mount this file system and provide correct access rights for your application. In the cloud instances this additional dependency onhugetlbfscauses additional troubles with mounting. Meanwhile since the Linux 2.6.32mmapsystem call provides easy and reliable interface for anonymous huge pages allocation. This issue stems from the backward compatibility with Linux 2.6.16.- The application must be built with the following linker flags:

common-page-size=2M max-page-size=2M. I understand that this’s the useful security requirement, so it’s just a little inconvenience. Having the ability to remap to huge pages any application for test purposes / quick performance estimation might be a very pleasant bonus for developers.

Some of the problems are critical. In other words, libhugetlbfs is not production ready. Oh…

Rolling up my sleeves higher and taking more air into my lungs, I began a slow and thorough dive into libhugetlbfs in order to make a server analogue for our MySQL, devoid of all these disadvantages, and also integrating the solution into the project code in the future.

How is a program loaded?

I’d like to put some restrictions on the following research: I deal with Linux 64-bit / ELF format / glibc.

To sort things out, it’s necessary to start our journey with describing of application launching algorithm in OS Linux, i.e. what is hidden behind execve system call? Yet again, there’re a lot of gorgeous articles which highlight all steps / functions in glibc / Linux kernel. For example, here the GNU ls invocation in bash is shown in details.

From all that plethora of technical information, I’ll focus on the following:

execvefor ELF file eventually callsload_elf_binaryinfs/binfmt_elf.cin Linux kernelload_elf_binary:- parses ELF file, search for code and data segments

- maps code and data segments to virtual memory, then HEAP segment is initialized right after the data segment

- maps VDSO segment

- looks for the current ELF interpreter (usually, it’s the dynamic linker from

glibc), then loads it into the memory (again: interpreter’s code and data are loaded to the memory)

- Linux kernel executes all other necessary functions, then all the information about just created mappings is saved on the stack, then the dynamic

glibclinker is invoked (or the application itself if interpreter is not specified, i.e. the binary is linked statically) - Dynamic linker (

glibc):- initializes the list of all mappings which were created by the kernel

- reads the DSO list, which the application depends on

- looks for the DSOs in the system (

LD_LIBRARY_PATH/RPATH/RUNPATH), then loads them and adds the meta information to the application’s list of all mappings - executes DSO constructors

- transfers the execution to the

mainfunction

So, the list of all application mappings are stored in:

- Linux kernel

glibclibrary

And the description of all these mappings is originally written in ELF file.

Linux kernel publishes the application mappings in /proc/$pid/smaps (detailed list) and /proc/$pid/maps (short list). Example for short list in Ubuntu 20.04 (kernel 5.4):

$ cat /proc/self/maps

555555554000-555555556000 r--p 00000000 08:02 24117778 /usr/bin/cat

555555556000-55555555b000 r-xp 00002000 08:02 24117778 /usr/bin/cat

55555555b000-55555555e000 r--p 00007000 08:02 24117778 /usr/bin/cat

55555555e000-55555555f000 r--p 00009000 08:02 24117778 /usr/bin/cat

55555555f000-555555560000 rw-p 0000a000 08:02 24117778 /usr/bin/cat

555555560000-555555581000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap]

7ffff7abc000-7ffff7ade000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7ffff7ade000-7ffff7dc4000 r--p 00000000 08:02 24125924 /usr/lib/locale/locale-archive

7ffff7dc4000-7ffff7dc6000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7ffff7dc6000-7ffff7deb000 r--p 00000000 08:02 24123961 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7ffff7deb000-7ffff7f63000 r-xp 00025000 08:02 24123961 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7ffff7f63000-7ffff7fad000 r--p 0019d000 08:02 24123961 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7ffff7fad000-7ffff7fae000 ---p 001e7000 08:02 24123961 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7ffff7fae000-7ffff7fb1000 r--p 001e7000 08:02 24123961 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7ffff7fb1000-7ffff7fb4000 rw-p 001ea000 08:02 24123961 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc-2.31.so

7ffff7fb4000-7ffff7fb8000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7ffff7fc9000-7ffff7fcb000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7ffff7fcb000-7ffff7fce000 r--p 00000000 00:00 0 [vvar]

7ffff7fce000-7ffff7fcf000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso]

7ffff7fcf000-7ffff7fd0000 r--p 00000000 08:02 24123953 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7ffff7fd0000-7ffff7ff3000 r-xp 00001000 08:02 24123953 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7ffff7ff3000-7ffff7ffb000 r--p 00024000 08:02 24123953 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7ffff7ffc000-7ffff7ffd000 r--p 0002c000 08:02 24123953 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7ffff7ffd000-7ffff7ffe000 rw-p 0002d000 08:02 24123953 /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ld-2.31.so

7ffff7ffe000-7ffff7fff000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

7ffffffde000-7ffffffff000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack]

ffffffffff600000-ffffffffff601000 --xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vsyscall]

The list of LOAD segments in ELF:

$ readelf -Wl /bin/cat

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

PHDR 0x000040 0x0000000000000040 0x0000000000000040 0x0002d8 0x0002d8 R 0x8

INTERP 0x000318 0x0000000000000318 0x0000000000000318 0x00001c 0x00001c R 0x1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2]

LOAD 0x000000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 0x0016e0 0x0016e0 R 0x1000

LOAD 0x002000 0x0000000000002000 0x0000000000002000 0x004431 0x004431 R E 0x1000

LOAD 0x007000 0x0000000000007000 0x0000000000007000 0x0021d0 0x0021d0 R 0x1000

LOAD 0x009a90 0x000000000000aa90 0x000000000000aa90 0x000630 0x0007c8 RW 0x1000

DYNAMIC 0x009c38 0x000000000000ac38 0x000000000000ac38 0x0001f0 0x0001f0 RW 0x8

NOTE 0x000338 0x0000000000000338 0x0000000000000338 0x000020 0x000020 R 0x8

NOTE 0x000358 0x0000000000000358 0x0000000000000358 0x000044 0x000044 R 0x4

GNU_PROPERTY 0x000338 0x0000000000000338 0x0000000000000338 0x000020 0x000020 R 0x8

GNU_EH_FRAME 0x00822c 0x000000000000822c 0x000000000000822c 0x0002bc 0x0002bc R 0x4

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 0x000000 0x000000 RW 0x10

GNU_RELRO 0x009a90 0x000000000000aa90 0x000000000000aa90 0x000570 0x000570 R 0x1

DSO dependencies:

$ ldd /bin/cat

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffff7fce000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007ffff7dba000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007ffff7fcf000)

Analysis of /proc/$pid/maps:

- libc.so.6 - it’s libc-2.31.so

- ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 - it’s ld-2.31.so

- linux-vdso.so.1 - it’s [vdso], virtual DSO provided by kernel to speedup 4 (for x86_64) system calls, more information is here

- [vvar] и [vsyscall] - obsolete implementation of [vdso] (kernel keeps backward compatibility)

- [heap] и [stack] - everything is clear

/usr/bin/cat- theLOADsegments fromreadelf, shifted in0x555555554000by kernel.

Right now you probably point out, that, hey, there’re 4 LOAD segments, but Linux shows 5 mappings. It’s all about GNU_RELRO technology (and the security again!): GNU_RELRO section contains PLT table on a separate page (default 4K in our example). It’s filled by dynamic linker. When job is done, it removes the write access from this page (or pages if PLT is bigger). Now if the application is trying to be hacked by replacing the address of some popular external function (e.g. printf@plt), the application will be sent a SIGSEGV signal. Checking the GNU_RELRO addresses:

- 0x55555555e000 - 0x55555555f000: 4K (mapping start/end, one 4К page)

- 0x555555554000 + 0xaa90 = 0x55555555ea90 (kernel’s shift +

GNU_RELROstart address) - 0x55555555ea90 & (~(0x1000 - 1)) = 0x55555555e000 (align previous result on 4K boundary => get the mapping start address)

- 0x55555555f000 - 0x570 = 0x55555555ea90 (from the end of

GNU_RELROsegment subtract the size of this segment => get unaligned mapping start address) - Numbers add up, and that’s good!

Brief description for readelf output:

- Offset = offset in ELF file

- VirtAddr = virtual address in application address space

- PhysAddr = physical address (have never used this field, interesting what is it needed for?)

- FileSiz = the size of ELF

datasection - MemSiz = FileSiz + (

.bsssegment: which is usually zeroed during the binary start)

To get application mappings from glibc, exploit dl_iterate_phdr function: manual. In fact, this API returns you the true 4 LOAD segments, exactly as in readelf output.

In total, armed with all information described above, I proceed to my main goal - remap LOAD segments.

Attempt 1

I use classical huge pages (not THP), size = 2M, my CPU is either AArch64 or x86_64.

I decided to name my newly born library elfremapper and mostly copy the main technology from the remap_segments function of libhugetlbfs. To make life easier, I’ll make my library static. Investigate the libhugetlbfs sources, do the same:

- Load all the LOAD segments via

dl_iterate_phdr(thank you,glibc, for accuracy in presented data: no magic withGNU_RELRO). - Check the segments don’t overlap (2M boundary aligned).

- Additionally align segments if ASLR is turned on (in this case the segments have the fixed shift of 0x555555554000 and an additional random shift that is uniquely generated by the kernel every time the application is launched - every address produced by kernel is, of course, 4K aligned).

- Allocate huge pages using

hugetlbfsfile system (for each LOAD segment create a separateMAP_PRIVATEmapping). - Copy each old mapping (4K based) to the new mapping (2M based):

mmap->memcpy->munmap. - Don’t close file descriptors, we need files to stay in memory.

-

Check the data is copied:

mmapthe first file descriptor (left open on previous step), read the data - and - there’s no data in this mapping!Well, the next step is reading the manual for

libhugetlbfsfrom official Linux kernel documentation and readingman mmap. The final conclusion is that data insideMAP_PRIVATEmapping is lost aftermunmap, because nothing is actually written to underlying file. It makes no difference what state of file descriptor is (opened or closed).man mmap:MAP_PRIVATE Create a private copy-on-write mapping. Updates to the mapping are not visible to other processes mapping the same file, and are not carried through to the underlying file. It is unspecified whether changes made to the file after the mmap() call are visible in the mapped region.Look more carefully to the

libhugetlbfssources. Yes, it usesMAP_SHAREDbeforememcpy. That seems quite unsafe, but there’s no other choice than making theMAP_SHAREDmapping too, meanwhile opened files are immediately removed (viaunlink) fromhugetlbfsbefore anything is written to them. Continue: - Check: data is copied, the file descriptors are left unclosed (remember: all files are unlinked).

-

Unmap all our current code and data mappings - and - get

SIGSEGVon the next code line followingmunmap.What’s wrong???

libhugetlbfsdoesmunmapand doesn’t crash, while my solution breaks apart. Thinking…When a code is executed, it is read by CPU from the same mapping as all others. The only difference is the execution permission (the mapping flag). It turns out that as soon as the code segment is removed from our virtual address space, reading the next assembly instruction is done from the address which does not belong to our process, and quite reasonably the

SIGSEGVis sent. Why doesn’tlibhugetlbfscrash? The point is thatlibhugetlbfsis supplied as DSO and, of course, it has its own separate mapping, which remains intact (I remap the main application’s mappings only).How to fix? Read

man mmap:MAP_FIXED Don't interpret addr as a hint: place the mapping at exactly that address. addr must be suitably aligned: for most architectures a multiple of the page size is sufficient; however, some architectures may impose additional restrictions. If the memory region specified by addr and len overlaps pages of any existing mapping(s), then the overlapped part of the existing mapping(s) will be discarded. If the specified address cannot be used, mmap() will fail.Well-well, so if I use

MAP_FIXEDandmmapover the existing mapping, the kernel removes it silently. That’s interesting. What if enter the system callmmapfrom the old mapping and exit having the new mapping using the old virtual addresses? Should work, checking: - Do not unmap the current mappings of code and data, utilize opened file descriptors (they point to

hugetlbfswith prepared memory) and makeMAP_SHARED+MAP_FIXEDmapping over existing ones (i.e.mmapconsumes both: base virtual address and file descriptor). It works! - Check

/proc/$pid/maps- instead of the application name, our LOAD segments are represented with something like/dev/hugepages/g4PcpN (deleted). That’s expected ifhugetlbfsis mounted on/dev/hugepagesand the temporary files are created bymktemp. Mission accomplished.

Small help: mounting hugetlbfs and huge pages allocation:

$ mkdir /dev/hugepages

$ mount -t hugetlbfs -o pagesize=2M none /dev/hugepages

$ sudo bash -c "echo 100 > /sys/kernel/mm/hugepages/hugepages-2048kB/nr_hugepages"

Summary:

- Remapping code is linked statically, i.e. it remaps itself at some execution point.

- I used

MAP_SHAREDfor code and data segments. “There will be consequences” - you might tell me with a smile, and you’re absolutely right! - How many huge pages are consumed? It appears, that the number of pages calculated from the ELF file and the number of consumed pages (

nr_hugepages-free_hugepages) are equal. That’s very important, because if there’s not enough huge pages, the error should be printed and, in general, the application must switch back to default system pages (usually 4K), i.e. put everything back.

Rewrite algorithm with “out of memory” handling:

- open file descriptor on

hugetlbfs, unlink the underlying file; - allocate huge memory via

mmapusing file descriptor; - check whether

mmapsucceeds, if not, print error, put everything already remapped back and stop; - copy our current segment (code or data) in recently allocated huge memory;

- unmap huge segment, leave file descriptor opened

- make the final

mmap(fixed|shared), intentionally overlap with current segment; - note: the final

mmapcall never fails with out of memory error, because the mapping is shared (no need to reserve additional memory in kernel), and all huge memory is already allocated on step 2 and checked on step 3.

Why MAP_SHARED for code/data is dangerous?

forkstops working. Not right word, it still works, but it does not copy shared mappings between child and parent (which makes sense). This causes race conditions between child/parent accessing the same data sections => sporadic unpredictable crashes => undefined behaviour.- New versions of

gdbstops working:gdb attachand loading ofcorefiles. Meanwhile old gdb versions still work, I don’t know why, there was no time to dig deeper.

Another global problem arise here, which I’d describe separately: remapping breaks symbol resolution in perf. As a result, perf top/perf record show you a wide range of disaggregated addresses instead of function names. Good or bad, perf exploits ELF files for symbol loading, exact ELF files are read from the same /proc/$pid/maps, which changed in our case. Fortunately, the trouble may be fixed easily using already existing perf features. Back in the day, when JIT compilers were invented (like in popular Java or Python), the perf was extended with JIT API: the symbols are loaded from /tmp/perf-$pid.map file which has plain clear format (3 columns: start address, size and symbol name). So, what should be done here is:

- compile a binary with debug symbols

- generate a file with symbols via

nm:$ nm --numeric-sort --print-size --demangle $app | awk '$4{print $1" "$2" "$4}' | grep -Ee"^0" > /tmp/perf-$pid.map

Attempt 2

MAP_SHARED haunts me. How to make the solution better? Take a detailed look into libhugetlbfs: the final mmap is executed with MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED (step 6 of our algorithm). Well, change MAP_SHARED to MAP_FIXED, check fork/gdb (it works!), run high load benchmarks. After ~3 weeks of different tests, the product crashes with SIGSEGV and the core dump is corrupted.

Detailed analysis:

MAP_PRIVATEleads to doubled huge page consumption. At the moment of finalmmap(remember, step 6) the kernel copies all shared pages to private pages (copy-on-write + reservation). At least, during the algorithm execution, the memory is consumed very intensively. In my case all the pages (x2 comparing to the previous version) are not returned to the OS until the application is stopped, even if all file descriptors are closed onhugetlbfs. After the remapping is done, there’s no need in shared pages anymore. Strange. Didn’t invest more time in it.- So, final

mmapleads to huge memory allocation, which means that “out of memory” error might occur. When there’s not enough huge pages,mmapreturnsENOMEMand next assembly instruction execution producesSIGSEGV. Reminds me something I saw before… Further investigation reveals thatmmapwith overlapping memory regions has obnoxious side-effect in case of errors. What happens:- kernel detects and discards the overlapping memory regions;

- then it tries to allocate huge pages, fails and returns

ENOMEMerror; - kernel does not return old memory region back, that’s why after

mmapsystem call the code section is lost!

Thinking…

libhugetlbfs doesn’t handle this error situation at all. If worse comes to the worst, the application is killed via SIGABORT by library itself. From the other side, the Google/Facebook/Intel products, based on THP, actively work with mremap. What if it can be used for huge pages too? The approach is very simple: create a private mapping backed with huge pages, copy segment content to it, then just move it to the new virtual address range (with overlap if needed).

Interesting. Try and get the error MAP_FAILED (EINVAL). Why?

If you look into Linux kernel source code, you’ll find that mremap system call still doesn’t support moving memory blocks backed with huge pages (https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/mm/mremap.c):

if (is_vm_hugetlb_page(vma))

return ERR_PTR(-EINVAL);

Bug fix is a rollback to MAP_SHARED mapping for code/data segments. Sadness eats me alive…

Attempt 3

Still, how to make the solution better? Looks like the first thought (“static libraries makes our lives easier”) in this particular case is fundamentally wrong. Well, let’s create our own DSO!

Now it’s allowed to delete the application code mapping and SIGSEGV doesn’t chase you, because the DSO code segment stays intact. Moreover, it’s possible to drop the hugetlbfs dependency, because we have relatively new kernel. As you probably already noticed, in the previous attempts, when the remapping code is linked statically, the hugetlbfs usage is mandatory. The reason is necessity of changing the mapping for the concrete virtual address range in one system call. That’s why when the mmap is used, its API is fully utilized: the virtual addresses and the file descriptor backed with hugetlbfs are specified. Applying new approach with DSO relaxes this limitation: several system calls could be executed and reliable error handling is possible, furthermore in bad cases putting the old mappings back looks like an easy job. Of course, on the other hand there’s always the itching idea to add a custom Linux kernel system call which can do all the magic instead of me, but for production purposes it’s not an option.

Change to algorithm to the following:

- Make anonymous 4K mapping with one aim only - force the kernel to find the empty space with appropriate size.

- Move (via

mremap) current working code and data mappings to the space allocated on the step 1 => I get overlapping address ranges and previously allocated memory block disappears without a single page fault; in addition, noSIGSEGVhere, because CPU is executing DSO code segment right now and nobody touches it. - Allocate anonymous huge memory on the old virtual address range (now this memory is vacant), call

mmap(private + fixed + huge2m). - If “out of memory” occurs, discard all huge memory, move old working code and data mappings back to the old virtual addresses and stop the algorithm, otherwise continue.

- Copy all content of old mappings to huge pages which have been just allocated.

- Remove old 4K mappings, return memory to the OS

As you can see, the DSO makes a difference. However, the pitfalls exist everywhere, so what to expect?

- GOT/PLT tables must be filled in advance, otherwise the

SIGSEGVreturns. The fact is thatglibcdynamic linker works in lazy mode by default. That means that it resolves the external function names only if they are used by the application or DSO. These tables are created inside LOAD segments of “consumers” (remember the story aboutGNU_RELGO?). Our own DSO uses some oflibcfunctions (mmap/mremap/memcpy), that’s why our own PLT/GOT tables are filled too. So by default if some function isn’t bound (the table entry is empty), the dynamic linker is invoked (actually, the empty entry contains jump instruction which eventually calls linker). If the dynamic linker is called in the middle of remapping process, theglibccode crashes somewhere inside. That’s weird, because theheapin my particular experiment was isolated (linker uses it for storing DSO list), the LOAD segment of our DSO is fixed and intact, only the main application segments are moved… Didn’t invest more time to figure out why it happens, if you know some details, please, share :) I was able to fix this issue quickly by adding-Wl,-znowlinker flag, which eventually notifies the dynamic linker to do all the job before any user code is executed. forkstarts working as expected, because code/data segments are private now. However,forkconsumes memory, and if during the system call the huge pages run out, the application getsSIGBUS. Well, it’s much better than undefined behaviour and memory corruption, but still not ideal. It’s definitely desired that in such cases the child, for example, switch back to default pages and continue to work as nothing happened. I must confess, I didn’t addSIGBUShandler or make other attempts to fix this case, to the moment this was discovered I was completely exhausted and just moved the remapping function to the place where theforkis already undoubtedly executed.THPcomes to mind: this technology should solve such cases automatically somewhere inside Linux kernel. Again, if you know how it works inside, shed the light to the issue.

NUMA

As is well known, each NUMA node allocates huge pages separately. Still don’t believe?

$ echo /sys/devices/system/node/node*/hugepages/hugepages-2048kB

Our Linux kernel deployed on servers with NUMA has very tricky and harsh behaviour. We use NUMA servers for cloud and each virtual machine is usually settled inside one NUMA node (/sys/fs/cgroup/cpuset/$vm/cpuset.mems). When mmap system call executes, the kernel scans all available huge pages on all NUMA nodes and if memory is enough (in total), the call succeeds. Then during the following page fault the kernel applies cgroup rules and tries to find huge pages on local NUMA node, can’t find them and sends SIGBUS to the application. As a result, the fancy error handling doesn’t work sometimes.

As a mitigation, the following scheme was invented:

- Roughly estimate the amount of VMs which could be settled on each NUMA node, then calculate and allocate a proper amount of huge pages statically for this particular NUMA node (via

nr_hugepages) - Additional consumption is covered by

overcommit hugepageswith a good reservation (let’s say 10 GB):echo 5120 > /sys/kernel/mm/hugepages/hugepages-2048kB/nr_overcommit_hugepages

overcommit hugepages allocates dynamically, so there’s the small nonzero possibility that the kernel can’t allocate the pages instantly, that memory might be fragmented, etc. Even though, it’s still makes sense to use such approach for long living processes like database servers. They usually restarted once in a month (e.g. the rolling update), and our remapping algorithm is executed during the process start only.

Saving the HEAP

Remember, when I iterated through the weaknesses of libhugetlbfs, I told you that the library might wipe out the HEAP segment from the application address space. Now I’ll tell you more about this process.

When we instruct linker to align LOAD segments in the ELF file on 2M boundary (common-page-size=2M max-page-size=2M), this process doesn’t touch HEAP segment. Everything is correct, kernel creates HEAP when the application starts, meanwhile linker works during compilation time. That means that [heap] has default 4K alignment and is “glued” to the last LOAD segment. When the last LOAD segment is remapped to the huge pages, its end is aligned on 2M boundary, which of course overlaps with [heap]. Then the last LOAD segment data is copied, but nobody copies the [heap] data. Furthermore, the remapping is done during the process start, which means that the [heap] is still quite small, so it often is totally located inside the last LOAD segment “tail”. The result is tragic:

- all data stored on the heap is lost;

- HEAP segment itself is lost - the

brksystem call starts always returningENOMEM.

Why does Linux kernel weed out [heap] completely from application address space if huge page entirely overlaps it - the open question. If you know, tell me, please :)

We solved this problem quite simple:

- read the

[heap]current begin/end addresses from/proc/$pid/maps, then if the last LOAD segment (2M aligned) overlaps with it, all the HEAP data is copied to the huge pages too; after the remapping all the virtual addresses stay the same, the data isn’t corrupted. - if

[heap]entirely overlaps with the last LOAD segment (2M aligned), it is artificially extended (manual call tobrk, size = 2M). That way some part of the HEAP segment survives after overlapping. It has been experimentally proven, that in this casebrkcontinues to work correctly,glibcmemory allocator works correctly too. What happens ifglibcallocator attempts to free the memory which was remapped to huge pages is unknown. I suspect thatbrkreturns error andglibchandles it correctly, because I have never detected crashes with such symptoms.

If you use a different allocator which utilizes mmap system call only (exploit anonymous pages, e.g. jemalloc), you’ll not face this problem at all.

Also, if ASLR is turned on, the kernel generates randomly shifted starting address for the [heap], which is usually located quite far from application LOAD segments (>2M), so this’s the rare case when ASLR solves the problems instead of adding them.

perf

Many words were written about what has been done, how to overcome pitfalls and finally build robustly working application. In addition, it was mentioned that technology increases performance (for MySQL server - TPS in OLTP tests). Nevertheless, it’s much better to observe the positive effects for CPU via perf tool. The thing is, each application has its own set of bottlenecks and applying our experience to your product may give you zero speedup, meanwhile perf always shows how the whole picture is changed from CPU perspective.

Analysis here is based on this article, in particular, I’m going to use the following table from official Intel documentation:

| Mnemonic | Description | Event Num. | Umask Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTLB_LOAD_MISSES.MISS_CAUSES_A_WALK | Misses in all TLB levels that cause a page walk of any page size. | 08H | 01H |

| DTLB_STORE_MISSES.MISS_CAUSES_A_WALK | Miss in all TLB levels causes a page walk of any page size. | 49H | 01H |

| DTLB_LOAD_MISSES.WALK_DURATION | This event counts cycles when the page miss handler (PMH) is servicing page walks caused by DTLB load misses. | 08H | 10H |

| ITLB_MISSES.MISS_CAUSES_A_WALK | Misses in ITLB that causes a page walk of any page size. | 85H | 01H |

| ITLB_MISSES.WALK_DURATION | This event counts cycles when the page miss handler (PMH) is servicing page walks caused by ITLB misses. | 85H | 10H |

| PAGE_WALKER_LOADS.DTLB_MEMORY | Number of DTLB page walker loads from memory. | BCH | 18H |

| PAGE_WALKER_LOADS.ITLB_MEMORY | Number of ITLB page walker loads from memory. | BCH | 28H |

Make the perf stat request for CPU metrics (let’s say, time duration is 30 seconds):

$ perf stat -e cycles \

-e cpu/event=0x08,umask=0x10,name=dwalkcycles/ \

-e cpu/event=0x85,umask=0x10,name=iwalkcycles/ \

-e cpu/event=0x08,umask=0x01,name=dwalkmiss/ \

-e cpu/event=0x85,umask=0x01,name=iwalkmiss/ \

-e cpu/event=0xbc,umask=0x18,name=dmemloads/ \

-e cpu/event=0xbc,umask=0x28,name=imemloads/ \

-p $app_pid sleep 30

For OLTP workload generation the sysbench is used, the sources are here. Then compile the MySQL 8.0 (for our case it’s 8.0.21).

Run server on NUMA0:

- Put database in /dev/shm (InnoDB / UTF8);

- Create 10 tables, 1M rows each (2.4 GB)

- CPU: Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6151 CPU @ 3.00GHz, no boost/turbo

- No ASLR

MySQL configuration details:

- innodb_buffer_pool = 88G

- innodb_buffer_pool_instances = 64

- innodb_data_file_path=ibdata1:128M:autoextend

- threadpool_size = 64

- performance_schema=ON

- performance_schema_instrument=’wait/synch/%=ON’

- innodb_adaptive_hash_index=0

- log-bin=mysql-bin

Then run sysbench (OLTP PS / 128 threads) on NUMA1:

$ sysbench \

--threads=128 \

--report-interval=1 \

--thread-init-timeout=180 \

--db-driver=mysql \

--mysql-socket=/tmp/mysql.sock \

--mysql-db=sbtest \

--mysql-user=root \

--tables=10 \

--table-size=1000000 \

--rand-type=uniform \

--time=3600 \

--histogram \

--db-ps-mode=disable \

oltp_point_select run

Workload is CPU-bound / read-only.

perf stat original server (TPS=581K):

3,213,429,932,057 cycles (57.15%)

194,753,410,016 dwalkcycles (57.14%)

139,241,762,335 iwalkcycles (57.14%)

3,977,146,385 dwalkmiss (57.14%)

4,969,951,701 iwalkmiss (57.14%)

15,102,884 dmemloads (57.14%)

30,794 imemloads (57.14%)

30.005683086 seconds time elapsed

perf stat after remapping code/data to huge pages (TPS=641K):

3,213,038,157,768 cycles (57.15%)

78,822,186,791 dwalkcycles (57.15%)

18,042,959,892 iwalkcycles (57.15%)

1,306,771,287 dwalkmiss (57.15%)

695,958,356 iwalkmiss (57.14%)

18,090,550 dmemloads (57.15%)

4,574 imemloads (57.15%)

30.005697688 seconds time elapsed

Compare:

iwalkcyclesdrops in 7.7 times,dwalkcyclesin 2.4 timeiwalkmiss- 7.1 times,dwalkmiss- 3 times- TPS: +10.3%

It should be acknowledged that applying compiler specific technologies, which significantly improves performance, decrease the positive effect from huge pages, however, it still exists. The reason is simple: all compilers seek to concentrate hot code in one place, which enhance cache usage inside all CPU components, including TLB.

Apply PGO/LTO/BOLT to the same MySQL 8.0.21 code (training workload is OLTP RW), run the same test.

perf stat without huge pages (TPS=915K):

3,212,892,465,135 cycles (57.14%)

175,161,815,648 dwalkcycles (57.15%)

64,908,489,131 iwalkcycles (57.15%)

3,579,819,559 dwalkmiss (57.15%)

2,108,905,920 iwalkmiss (57.15%)

21,031,821 dmemloads (57.15%)

85,002 imemloads (57.14%)

30.004624838 seconds time elapsed

perf stat with huge pages for code/data (TPS=952K):

3,213,313,736,349 cycles (57.15%)

92,547,731,364 dwalkcycles (57.15%)

22,334,822,336 iwalkcycles (57.15%)

1,611,692,765 dwalkmiss (57.15%)

804,414,164 iwalkmiss (57.14%)

25,627,581 dmemloads (57.12%)

15,717 imemloads (57.12%)

30.006456928 seconds time elapsed

Compare:

iwalkcyclesdrop in 2.9 times,dwalkcyclesdrop in 1.9 timeiwalkmiss- 2.6 times,dwalkmiss- 2.2 times- TPS: +4%

Summary: our aircraft has successfully taken off, the flight is normal:

What’s next?

Well, the technology of remapping code and data sections to huge pages has right to life given the current state of Linux kernel API and glibc library. Although, after thinking over everything written here, one simple idea comes to my mind. Why do I need to remap anything? Why not to create the huge mapping in the first place?

Daniel Black from the MariaDB offered the simple and elegant solution - make all the work right inside the glibc dynamic linker. I can see here only one obstacle - how to start the application? By default, its LOAD segments are loaded by kernel, and changing the kernel is something I want to steer clear of. Meanwhile, the dynamic linker is capable of running applications by itself! Have you ever tried to run dynamic linker as an application? Yeah, it’s the DSO indeed, but at the same time it’s runnable too:

$ /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

Usage: ld.so [OPTION]... EXECUTABLE-FILE [ARGS-FOR-PROGRAM...]

You have invoked `ld.so', the helper program for shared library executables.

This program usually lives in the file `/lib/ld.so', and special directives

in executable files using ELF shared libraries tell the system's program

loader to load the helper program from this file. This helper program loads

the shared libraries needed by the program executable, prepares the program

to run, and runs it. You may invoke this helper program directly from the

command line to load and run an ELF executable file; this is like executing

that file itself, but always uses this helper program from the file you

specified, instead of the helper program file specified in the executable

file you run. This is mostly of use for maintainers to test new versions

of this helper program; chances are you did not intend to run this program.

...

$ /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 /bin/echo "HELLO, WORLD"

HELLO, WORLD

Advantages of this approach are undeniable:

- no need to write additional code to application or create a separate DSO

- huge pages for LOAD segments is available not only for application but for any other DSO loaded by dynamic linker

- loading DSO to huge pages becomes dynamic: the same code is invoked in both cases - while application starts and inside

dlopencall.

Attempt to create a “dirty” patch for our local glibc fork revealed only one nasty feature - excessive memory consumption. The fact is, the ordinary system DSOs have very small LOAD segments. From time to time, even 4K page is superfluous for them, I don’t speak about 2M page. Moreover, each system DSO has several LOAD segments inside (remember about security). As a result, too much memory is wasted. For most of the ordinary system DSOs the default 4K pages is a nice fit, standard 4K TLB records make job done perfectly. That’s why for dynamic linker a special filter is needed, for example, an environment variable with the list of DSOs which are needed to be put on huge pages along with application itself.

Well, if I get free time, I’ll finish my work with dynamic linker and tell you more about my adventures in the glibc community. People talk contributing the patch to glibc main source tree is a nontrivial and extremely hard task.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to say many thanks to the Cloud DBS team in Huawei Russian Research Institute, which took a great part in active design, research and code review.

To the reader

If you have some comments or observations, you’ve found a clear error or typo, there’s missed reference or the copyright is violated, please, leave a note or notify me by all available means, I’d be happy to fix, refine or append the article.

Source code, forged with blood and sweat, is published here.

References

- https://wiki.debian.org/Hugepages

- https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/vm/hugetlbpage.txt

- https://www.1024cores.net/home/in-russian/ram---ne-ram-ili-cache-conscious-data-structures

- https://medium.com/applied/applied-c-memory-latency-d05a42fe354e

- https://yandex.ru/images

- https://e7.pngegg.com/pngimages/908/632/png-clipart-man-wearing-black-jacket-illustration-morpheus-the-matrix-neo-red-pill-and-blue-pill-youtube-good-pills-will-play-fictional-character-film.png

- https://alexandrnikitin.github.io/blog/transparent-hugepages-measuring-the-performance-impact/

- https://www.percona.com/blog/2019/03/06/settling-the-myth-of-transparent-hugepages-for-databases/

- https://bugs.mysql.com/bug.php?id=101369

- https://jira.mariadb.org/browse/MDEV-24051

- https://0xax.gitbooks.io/linux-insides/content/SysCall/linux-syscall-4.html

- https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man7/vdso.7.html

- https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/dl_iterate_phdr.3.html

- https://github.com/dmitriy-philimonov/elfremapper

- https://github.com/akopytov/sysbench

- https://i1.wp.com/freethoughtblogs.com/affinity/files/2016/06/facepalm_estatua.jpg

- https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EroZF0DXYAIDYI4.jpg

- https://i.ytimg.com/vi/6K8hc4aFwCg/maxresdefault.jpg

Comments