Simulation of thread pool for database server

This is a blog post version of our paper “Simulation of thread pool for database server” that will be published in CEUR Workshop Proceedings. In the article, we consider an object-oriented simulation model for thread pool. The implementation of thread pool in MariaDB and Percona Server was taken as a basis. Model’s input flow and their distributions are described. Model’s output results are consistent with known “concurrency level – throughput” dependency patterns for IO- and CPU-bound workloads. The model is written in C++ and its software architecture is also considered, including provided classes, methods and call graph. The model takes into account “thread contention” phenomena and mathematical expressions for it were proposed. The built model has a practical value as an effective tool for static and dynamic analysis of the most significant parameters affecting performance and optimal choice of these parameters.

Introduction

Simulation is known to be an effective decision-making tool in a wide range of applied problems such as industry, transport, medicine and military science. However, the use of simulation as “computer science for itself” is equally important. There are a lot of examples how to use simulation in software development and design of complex IT-systems. One of such system is thread pool, which is has been implemented in various software systems over the past 25 years. The concept of thread pool is an alternative to rule “one connection – one thread”. It allows not only to save resources, but also to improve the performance of a whole software product in general. The basic idea is to re-use already existing thread for handling of new task. There are several thread pool implementations and [10] contains the most extensive review of them. There are also a lot of documentation about specific ones. So, one of the first thread pools was described in [14] for broker of object queries. Thread pools for Android and application server Oracle GlassFish are described in [1] and [11] respectively. [26] contains an effective example of using of Python thread pool for difficult scientific problem. Microsoft CLR thread pool is described in fundamental work [18] and the most recent open- source implementation is available in [24]. Java threading specific extension is proposed in scientific research [25]. DBMS developers also pay much attention to this feature, in particular, MySQL[15], MariaDB[20], Percona Server[13]. The distinctive features of these thread pools are the following:

- Connections are put into a thread group at connect time on a round-robin basis. The number of thread groups is configurable.

- Each thread group tries to keep the number of active threads, being executed on CPU, to one or zero. If a query is already executing in the thread group, put the connection in the wait queue.

- Put waiting connections into the high priority queue when a transaction is already started on the connection.

- Allow another query to execute if the queue is not empty and there are no completed queries during the specified time interval. It is provided by special thread called Timer.

The paper is focused only on the model of this thread pool variety. All thread pools contain many parameters, which are assigned by a developer or DBA and affect the final thread pool performance. The main parameter is thread pool size (tp-size) that is also concurrency level. The number of thread groups plays this role in above- mentioned DBMS implementations. The choice of tp-size depends on many factors, such as CPU number, memory volume, number of concurrent client requests, but the finest is so-called workload profile. It should be noted that optimal values of tp-size are significantly different for CPU-bound and IO-bound workloads even if the number of connections to the server is the same [22]. Many articles contain recommendations how to choose tp-size in a simple way. Examples are [1], [7], [8], [11], [12], where suggestions are based on the number of CPU cores, average request latency on CPU, average off-CPU time and well-known in queueing theory Little’s law. However, these approaches does not allow to maximize throughput and Microsoft specialists achieved the greatest success in this way. Articles [5], [6] consider the use of HillClimbing optimizer for the choice of tp-size, [21] contains test results. Work [4] describes the variety of HillClimbing, which is based not on gradient decline, but on signal processing approach, because it is more stable to the influence of random fluctuations. Other algorithms for tp-size calculation are proposed in [10] and [19]. The most recent work [19] contains full and actual reference list for this problem. At the same time, a simulation model can help to get a deep understanding how thread pool does work. So, thread pool performance (expressed, for example, in transactions per second) depends not only on tp-size, but on other parameters. To clear how each parameter affects, many long-time and expensive experiments are needed on working servers. However, a smart simulation model can do that much faster, which is the main advantage of simulation for any task. It should be said that simulation approach is tested rather weakly now days. Work [2] uses too specific and rare tool, the recent work [17] of Ukrainian specialists applies stochastic Petri nets to simulate thread pool. Our paper proposes thread pool simulation model where implementation from [13] is taken as basis. The model is written in C++ with methodology described in [27], which allows to cover flexibly all algorithmic features of the system in full. The thread pool itself is described in section 2, section 3 contains the software architecture of the proposed model. Some results of the model’s validation are exposed in section 4 and section 5 contains conclusions and suggestions how to use the model.

Description of simulated thread pool

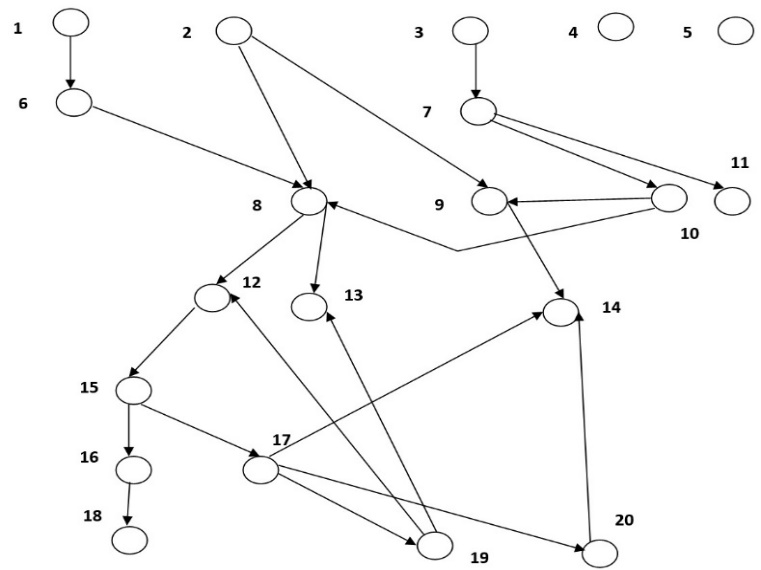

Neglecting secondary details, a thread pool call graph looks like this (Fig. 1), where designations corresponds to the following functions (Table 1).

Figure 1: Thread pool call graph

Figure 1: Thread pool call graph

Table 1. Thread pool functions

| Name | Description | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

1 add_connection |

Add a new connection, choose thread group for it | 11 timeout_check |

Check, if the connection has expired (request took too long time); if yes, delete connection |

2 wait_begin |

Callback for the start of off-CPU round | 12 create_worker |

Create a new thread |

3 start_timer |

Start a timer thread to track stalled threads | 13 wake_thread |

Wake an idle thread |

4 set_tp_size |

Set the thread pool size | 14 too_many_threads |

Check if there are too many active threads in group |

5 wait_end |

Callback for the end of off-CPU round | 15 worker_main |

Main function for thread from thread pool |

6 queue_put |

Put a new connection into queue | 16 handle_event |

Preparing to serve a request |

7 timer_thread |

Main function for the timer thread | 17 get_event |

Assign a connection to ready thread (make it active) |

8 wakeCreateThread |

Create a new thread or wake idle | 18 process_request |

Serve a request by thread |

9 queues_are_empty |

Check queues | 19 listener |

Thread for polling, repeatedly extract connection from thread group’s open file descriptor |

10 check_stall |

Treat stalled threads | 20 queue_get |

Extract a connection from queue |

Description of simulation model

Let’s list the input values for model, which are produced by a random number generator with the given distribution:

-

the input flow of connections: the distribution of time intervals between

add_connection()calls; -

the time of new thread creation: timing for

create_worker(); -

the duration of one active round for thread: the time from the start of request serving till the first

wait_begin()call; or betweenwait_end()andwait_begin()calls; or betweenwait_end()call and request completion; -

the duration of one off-CPU round for thread: the time between

wait_begin()andwait_end()calls; -

the number of active rounds during one request serving;

-

the time interval between request completion and selection of the same persistent connection by polling to assign it new thread and start the next request.

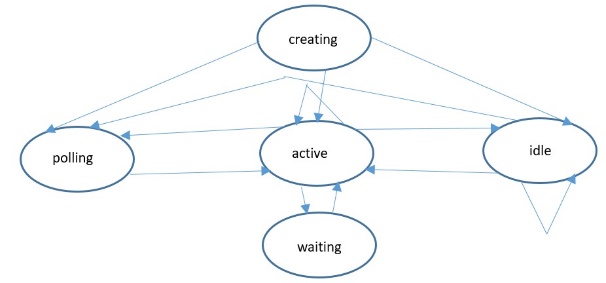

The output of model is the average number of served queries per second and the average latency of one request serving. The model is built on the following classes: Threadpool (singleton), Threadgroup, Connection, Thread, Timer (singleton). States for Thread instances are the following:

-

Creating – thread creation;

-

Active – request serving;

-

Waiting – input-output waiting;

-

Idle – previous request is completed, but the next is not assigned yet;

-

Polling – only one thread can be at this state by the moment. This thread is responsible for polling (performs

select()API) and called listener.

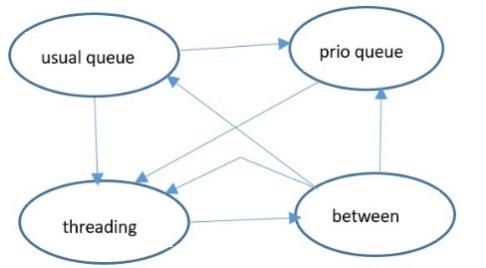

States for Connection instances are the following:

-

in usual queue – connection is waiting for thread assignment in usual queue;

-

in prio queue – connection is waiting for thread assignment in priority queue (if connection is related to already open transaction);

-

threading – thread is assigned to connection, request is being served;

-

between – request is completed, connection is waiting for repeated extraction by thread-listener.

Possible transitions are shown on Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2: State transitions for Thread class Figure 2: State transitions for Thread class |

Figure 3: State transitions for Connection class Figure 3: State transitions for Connection class |

In addition to tp-size there are several parameters which we can play to obtain greater performance:

-

oversubscribe – defines maximum number of active threads in one group;

-

timer_interval – the time interval before activities of Timer thread;

-

queue_put_limit – wake or create thread in

queue_put()if the number of active threads in group is less or equal to this parameter; -

woct_top_limit – create new thread in

wake_or_create_thread()only if the number of active threads in the group is less or equal to this parameter; -

create_thread_on_wait – Boolean parameter. Define would new thread be created in

wait_begin(); -

idle_timeout – maximum time thread can be in idle state;

-

listener_wake_limit – listener wakes an idle thread if number of active threads is less or equal to this parameter;

-

listener_create_limit – listener creates a new thread if the number of active threads is less or equal to this parameter.

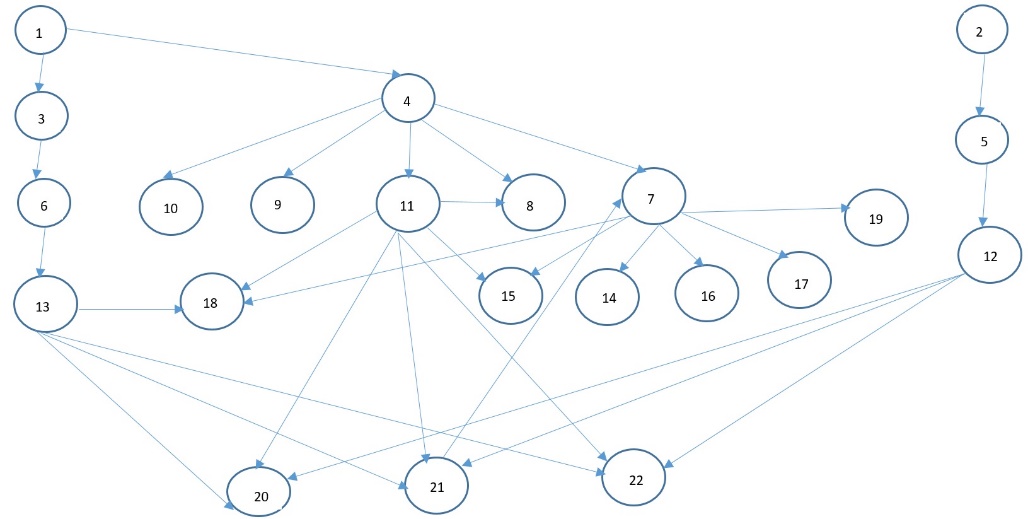

Model call graph is shown on Fig.4.

Titles of methods are listed in Table 2. The main loop of model is written in Listing 1.

Table 2. Classes and methods

| Class::method | Class::method |

|---|---|

Threadpool::run |

12. Threadgroup::check_stall |

Timer::run |

13. Threadgroup::queue_put |

Threadpool::add_connection |

14. Threadgroup::queue_get |

Threadgroup::run |

15. Connection::to_threading |

Threadpool::check_stall |

16. Thread::to_polling |

Threadgroup::add_connection |

17. Threadgroup::get_connection_from_polling |

Threadgroup::assign_connection_to_thread |

18. Connection::to_usual_queue |

Thread::to_active |

19. Thread::to_idle |

Thread::to_waiting |

20. Connection::to_prio_queue |

Connection::to_between |

21. Threadgroup::wake_thread |

Threadgroup::listener |

22. Threadgroup::create_worker |

Listing 1.

#define NUMBER_OF_TACTS 60000000 /*in mcs */

int main() {

Threadpool *tpl = Threadpool::getInstance();

Timer *tmr = Timer::getInstance();

/*initialize random number generator*/

srand((unsigned)time(0));

for (long i = 0; i < NUMBER_OF_TACTS; i++) {

Tpl->run();

Tmr->run();

}

delete tpl;

delete tmr;

return 0;

}

Now let’s consider how model takes into account time consumption of CPU switches from one thread context to another. This phenomena is known as thread contention and it is the reason of performance degradation when the number of groups has reached some threshold value. If we do not take it into account, we will simulate not a life, but something else and our results will cost nothing. Let’s $N$ is the number of active threads, $M$ is the number of CPU cores, $M < N$, $a$ is the switching time (model parameter), $t$ is time of request serving (request length in terms of queueing theory). Then model time goes ahead for all requests in one tick not on 1, but on $\frac{M}{N} -a$ value. So, $N$ requests will be completed on time $\frac{tN}{M-aN}$ and performance equals $\frac{M-aN}{t}$ requests per one time unit. We can see that it actually decreases when $N$ increases. Thus, we can formulate the following rule: if condition

\[M - aN > \frac{N}{\lceil\frac{N}{M}\rceil}\]is true, the residual length is reduced on $\frac{M}{N}-a$ for all $N$ active threads. Otherwise we act as follows: take arbitrary $M$ active threads from $N$ and decrement residual length for each of them, and residual length remains untouched for the rest $M-N$ active threads. The second case means that CPU switching time of thread context is too long, so, the using of CPU sharing is not sensible. Truncated square brackets in condition mean division with upward rounding.

Model validation and results

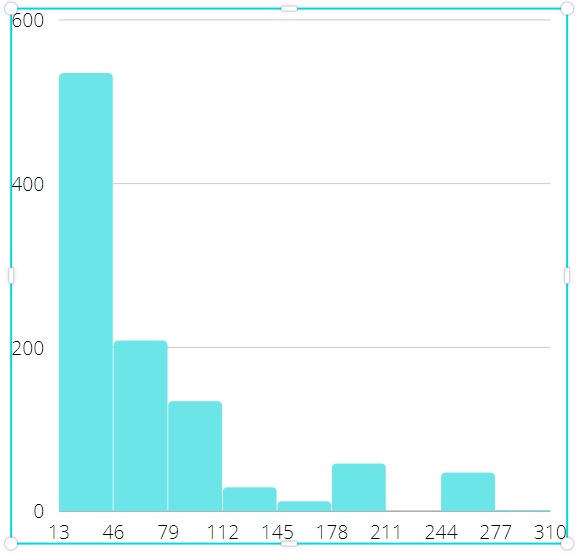

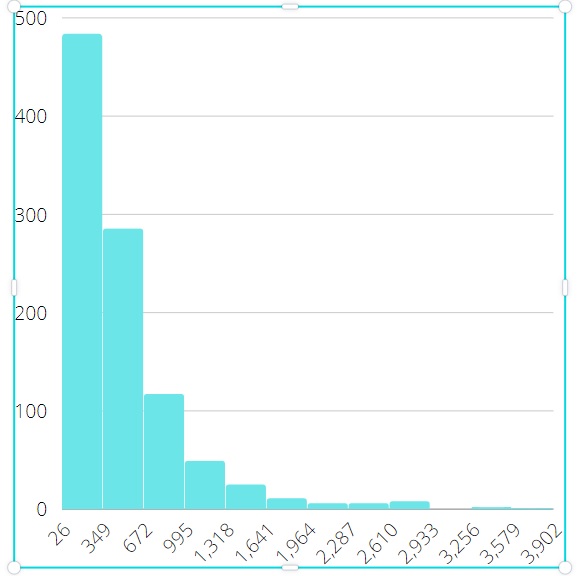

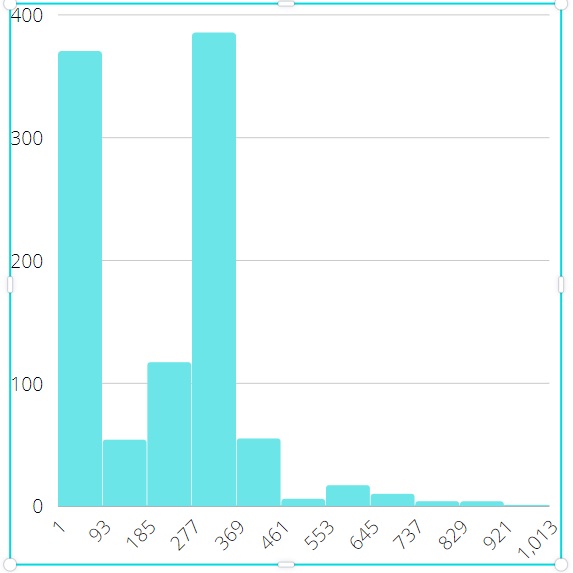

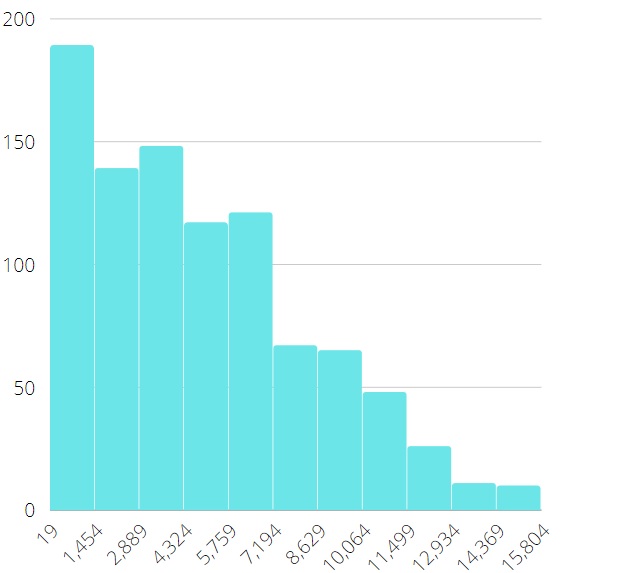

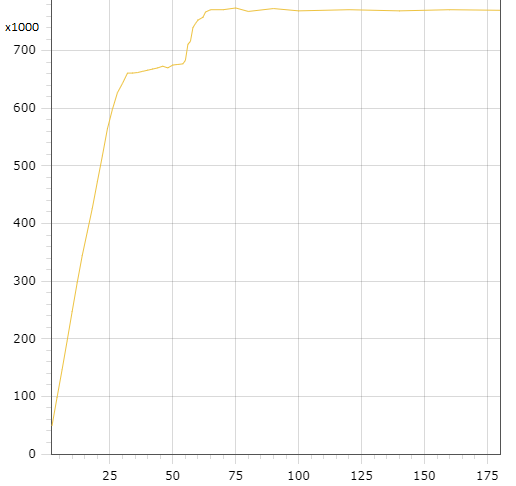

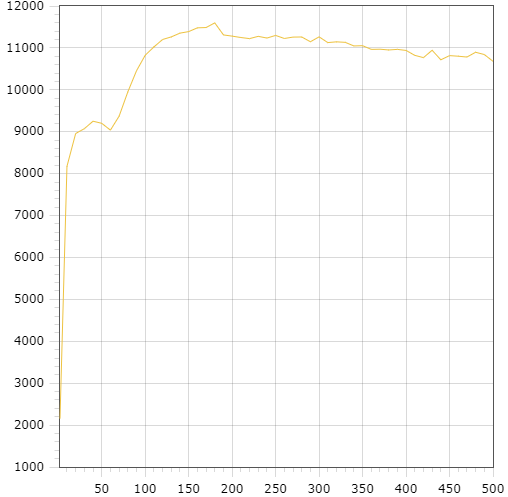

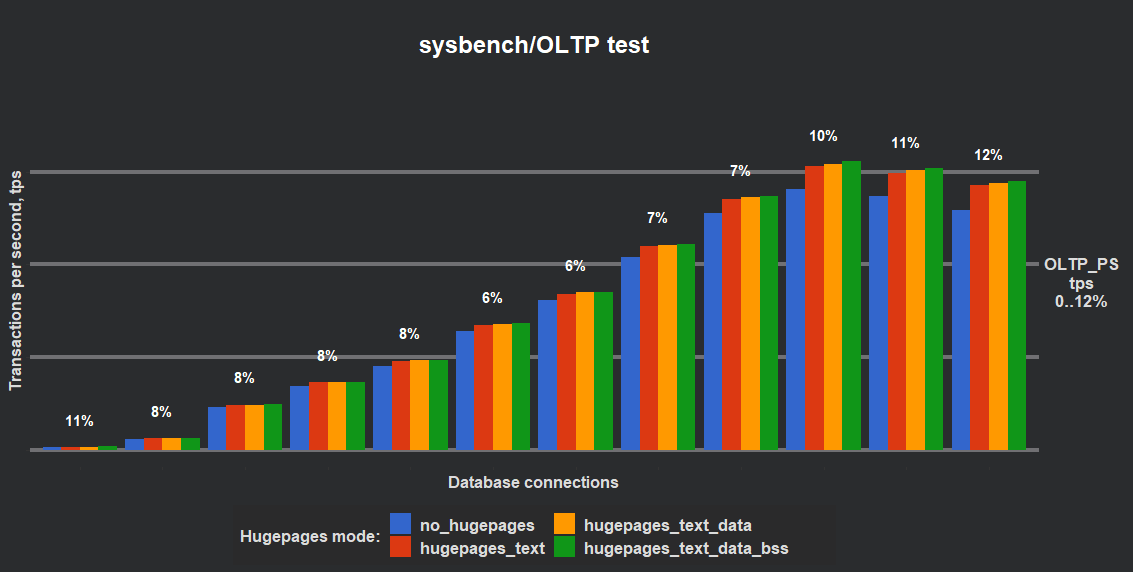

Validation of model was performed as follows. First, we got output results (average queries per second and latency) on working MySQL server with widely known testing utility sysbench [9] written by one of the authors of this paper. At the same time all measurements were logged during this experiment to build all necessary input distributions for simulation model. Then these distributions were used in simulation model and its output results were compared with results of sysbench. Model has shown the most divergence not greater than 2% for all sequence of experiments. In this section we emphasize on comparison of results CPU-bound and IO-bound workloads. Here are examples on differences in input data. Figures 5 and 6 show histograms for CPU active round latency in microseconds, the length of sample is 1000. In other words, that is the timing of state active for thread instances in terms of our model. Figures 7 and 8 show histograms for off-CPU round latency in microseconds, which is the timing of state waiting for thread instances. Data for CPU-bound workload were collected with 1024 concurrent connections and data for IO-bound workload were collected with 128 ones. We can see that off-CPU round for IO-bound workload is much longer than for CPU-bound, because the rate of IO-actions is higher. It means that tp-size which is greater than the number of CPUs, can result in valuable performance effect. Data for figures 9 and 10 are collected with model. The figures show dependencies of thread pool performance on number of thread groups. The duration of simulation is 60 million ticks (mcs), the number of CPUs is 72. These pictures quite correspond to known patterns, classified, for example, in [3] . We can see that tp_size > 72 gives nothing for CPU-bound workload, because CPUs are ever busy just the same. That is why the main goal of model is not so much to increase performance but to minimize tp-size. However, we have other situation for IO-bound workload. Performance continues to increase even after tp-size=72, achieving the maximum near the value tp-size=180, then starting to decrease since thread contention. This is the typical case for IO-bound workload and high concurrent connections.

Conclusions

Let’s formulate where thread pool simulation model could be applied:

-

to reveal parameters and local algorithmic decisions to which thread pool performance is most sensitive and to suggest server tuning recommendations, which could be useful for software engineer and DBA;

-

to reveal dependencies of model output on input distributions;

-

to find optimal values of parameters and to reveal their dependencies on quantitative and qualitative indicators of server workload;

-

dynamic optimization: to collect and treat statistics on working DBMS server with subsequent run of model for the quick search of optimal tp-size and other important parameters.

And finally a few words about ML approach in database and how simulation can help. This approach is actively investigated in the last years [23]. The situation is following. Some separate software module (for example, thread pool) is configured by several parameters, chosen by developers or DBA. As all set of these parameters in total as each of them in particular affect the output which is some performance measure. Thus, some tuple of parameters’ values gives the maximum performance, so, the goal is to find the optimal tuple of parameters. The optimal tuple varies in wide range depending on various items, such as:

-

server’s hardware configuration (number and types of CPU, volume of RAM and swap partition, etc.); operation system and job scheduling algorithms;

-

current load from clients in sense of quantity (number of simultaneous connections);

-

current load from clients in sense of types (distribution of request length and availability of consumed resources, such as CPU and disk).

To find the optimal tuple simulation model can be applied. Found optimal tuple corresponds to some fixed workload profile on the given server. If we describe this profile more or less completely, we can expect that next time when profile will be approximately the same we have already known optimal tuple. Just this idea is the cornerstone of proposed approach. The general plan is:

-

to profile the DBMS code in proper way and collect workload input data;

-

to find optimal tuple for collected input data with simulation model;

-

to put found optimal tuple into the correspondence of collected data, thus getting the new record of train dataset;

-

when a training dataset will become large enough we train our ML model on it, then try to apply this model on working DBMS server.

According to [16], we can perform ML-procedures just in database by means of proposed SQL-language extension. We do not need address the external ML tool after extraction of train dataset from the database. It seems that being implemented, results of this work will significantly improve the efficiency of described approach.

Results of simulation model application will be published in the next articles.

References

1: Better performance through threading. – URL: https://developer.android.com/topic/performance/threads

2: F. S. Boer, I. Grabe, M. M. Jaghoori, A. Stam, W. Yi, Modeling and Analysis of Thread-Pools in an Industrial Communication Platform. – ICFEM’09: Proceedings of the 11-th International Conference on Formal Engineering Methods, November 2009, pp.367-386. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10373-5_19.

3: X. Dongping, Performance study and dynamic optimization design for threadpool systems (2004). – URL: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc780878/m2/1/high_red_d/85380.pdf

4: E. Fuentes, Concurrency – Throttling Concurrency in the CLR 4.0 Threadpool (September 2010). – URL: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/archive/msdn-magazine/2010/September/concurrency-throttling-concurrency-in-the-clr-4-0-threadpool

5: J. L. Hellerstein, V. Morrison, E. Eilebrecht, Applying Control Theory in the Real World. – ACM’SIGMETRICS Performance Evaluation Rev., Volume 37, Issue 3, 2009, pp.38-42. doi: 10.1145/1710115.1710123.

6: J. L. Hellerstein, V. Morrison, E. Eilebrecht, Optimizing Concurrency Levels in the .NET Threadpool. – FeBID Workshop 2008, Annapolis, MD USA.

7: A. Ilinchik, How to set an ideal thread pool size (April 2019). – URL: https://engineering.zalando.com/posts/2019/04/how-to-set-an-ideal-thread-pool-size.html

8: Java Concurrency in lock optimization and optimization thread pool. – URL: https://programmersought.com/article/84012626442

9: A. Mughees, How to benchmark performance of MySQL using Sysbench (June 2020). – URL: https://ittutorial.org/how-to-benchmark-performance-of-mysql-using-sysbench

10: S. Nazeer, F. Bahadur, Prediction and Frequency Based Dynamic Thread Pool System. – International Journal of Computer Science and Information Security, Vol. 14, No. 5, May 2016, pp.299-308.

11: Oracle GlassFish Server 3.1 Performance Tuning Guide. – URL: https://docs.oracle.com/cd/E18930_01/pdf/821-2431.pdf

12: K. Pepperdine, Tuning the Size of Your Thread Pool (May, 2013). – URL: https://infoq.com/articles/Java-Thread-Pool-Performance-Tuning

13: Percona Server for MySQL: Thread Pool. – URL: https://www.percona.com/doc/percona-server/5.7/performance/threadpool.html

14: I. Pyarali, M. Spivak, R. Cytron, Evaluating and Optimizing Thread Pool Strategies for Real-Time CORBA. – ACM’SIGPLAN Notices, Volume 36, Issue 8, August 2001, pp. 214-222. doi:10.1145/384198.384226.

15: Ronstrom M. MySQL Thread Pool: Summary (October 2011). – URL: https://mikaelronstrom.blogspot.com/2011/10/mysql-thread-pool-summary.html

16: M. Schüle, F. Simonis, T. Heyenbrock, A. Kemper, S. Günnemann, T. Neumann, In-Database Machine Learning: Gradient Descent and Tensor Algebra for Main Memory Database Systems. - In: Grust, T., Naumann, F., Böhm, A., Lehner, W., Härder, T., Rahm, E., Heuer, A., Klettke, M. & Meyer, H. (Hrsg.), BTW 2019. Gesellschaft für Informatik, Bonn. pp. 247-266. – URL: https://dl.gi.de/bitstream/handle/20.500.12116/21700/B6-1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y doi: 10.184.20/btw2019-16.

17: I. Stetsenko, O. Dyfuchyna, Thread Pool Parameters Tuning Using Simulation. – In book: Advances in Computer Science for Engineering and Education II (editor Hu Z.), Springer 2020, pp.78-89. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-16621-2_8

18: R. Terrell Concurrency in .NET: Modern patterns of concurrent and parallel programming. – Simon and Schuster Publishing House, 2018, 568 pp.

19: J. Timm, An OS-level adaptive thread pool scheme for I/O-heavy workloads. – Master thesis, Delft University of Technology, 2021. URL: https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid%3A5c9b4c42-8fdc-4170-b978-f80cd8f00753

20: Thread Pool in Maria DB. URL: https://mariadb.com/kb/en/thread-pool-in-mariadb

21: M. Warren, The CLR Thread Pool ‘Thread Injection’ Algorithm (April 2017). – URL: https://codeproject.com/Articles/1182012/The-CLR-Thread-Pool-Thread-Injection-Algorithm

22: What is the ideal Thread Pool Size – Java Concurrency. – URL: https://techblogstation.com/java/thread-pool-size

23: X. Zhou, J. Sun, Database Meets Artificial Intelligence. – IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, May 2020. doi: 10.1109/TKDE.2020.2994641.

24: URL: https://github.com/dotnet/coreclr/blob/master/src/vm/win32threadpool.cpp

25: M. S. Akopyan, Using multithreaded processes in ParJava environment. - Proceedings of the Institute for System Programming of the RAS (Proceedings of ISP RAS). 2015;27:2 (In Russian). – URL: http://www.mathnet.ru/links/a7d9a523f1eb29a3745bd7209c3765aa/tisp119.pdf doi: 10.15514/ISPRAS-2015-27(2)-1.

26: V. A. Klyachin, Parallel Algorithm of Geometrical Hashing Based on NumPy Package and Processes Pool. – Vestnik Volgogradskogo Universiteta, seriya 1, Mat.-Fiz., 2015, issue 4 (29), pp. 13-23, (in Russian). – URL: https://www.mathnet.ru/links/465bab7745fcdb80f25de7c0f18b0a07/vvgum71.pdf doi: 10.15688/jvolsul.2015.42.

27: I. I. Trub, Object-oriented simulation on C++. – Piter Publishing House, 2005. – 416 p. (in Russian). – URL: https://inftechgroup.ucoz.com/load/knigi_po_programmirovaniju/obektno_orientirovannoe_programmirovanie/obektno_orientirovannoe_modelirovanie_na_c/2-1-0-43 ISBN: 5-469-00893-2.

Comments